I. The Desert’s Woven Poetry: An Introduction to the Bhujodi Saree

The Bhujodi saree is a masterpiece of Indian handloom textiles, a cultural artifact that is deeply intertwined with the landscape and heritage of Kutch, Gujarat. Originating from the small village of Bhujodi, located just 8 kilometres southeast of the city of Bhuj, this textile is not merely a garment but a “piece of living heritage” that carries a 500-year-old story. In this sun-scorched terrain, time seems to move to the rhythmic clatter of the loom, and every thread spun tells a tale of resilience, community, and artistry.

At the heart of this ancient craft lies the Vankar community, whose name literally translates to “weaver”. As specialists in weaving, the Vankar have served for centuries as the master artisans and “guardians of a vanishing art”. Their skills were not born in Kutch, but were brought with them generations ago when they migrated from Sindh. This migration established a legacy of motifs and techniques that continue to define the Bhujodi saree today. It is important to note that the Vankar, though a professional caste, are part of the larger Meghwal community, a detail that adds nuance to their cultural identity beyond their craft.

The essence of an authentic Bhujodi saree lies in its defining characteristics, which set it apart from mass-produced imitations. The most significant of these is the extra weft weaving technique, which creates raised, embroidery-like patterns directly on the fabric. Furthermore, the genuine article possesses a unique

hand feel—it is breathable and slightly uneven—and its intricate designs are seamlessly mirrored on both sides of the fabric, a testament to the weaver’s skill and the absence of printing. The deep exploration of these technical and aesthetic traits is fundamental to understanding the profound value of the Bhujodi saree, which is far more than a simple piece of cloth; it is a wearable history.

II. Threads of a Nomad’s Life: Bhujodi Saree | The Historical and Cultural Tapestry

The historical foundation of Bhujodi weaving is built on a remarkable and mutually beneficial relationship between two distinct communities. The Vankar weavers entered into a time-honoured covenant with the Rabari pastoral nomads, a tribe believed to have migrated to the region from Afghanistan over a millennium ago. For centuries, the Rabari relied on the Vankar for survival in the harsh desert climate. They provided the weavers with raw, hand-spun wool sheared from their sheep and goats. In return, the Vankar would transform this coarse fibber into heavy, protective woollen blankets (dhablas) and veils (loodi) that were essential for the Rabari to endure the extreme temperatures of Kutch.

This historical arrangement reveals a profound truth about the Bhujodi weave: it originated as a collaborative canvas rather than a singular finished product. While the Vankar meticulously crafted the foundational fabric, the Rabari tribes would then take the woven material and “embroider exquisite and unique patterns on it to symbolize their community”. This means that the Bhujodi textile tradition was not an isolated art form but an integral component of a broader cultural and artistic ecosystem. The final piece was a multi-layered testament to inter-community trust and a shared heritage, where the weaver’s loom provided the very ground on which another artist’s needle would dance.

Over time, this ancient trade began to wane, primarily due to the advent of power looms and the influx of cheap, mill-made fabrics that arrived in the 1950s. The Vankar, facing the very real threat of their craft becoming extinct, demonstrated an incredible capacity for adaptation. They pivoted their skills from weaving utilitarian blankets to crafting fine cotton and silk sarees, shifting their focus to cater to the local population and emerging commercial markets.

However, the greatest challenge to the craft’s survival arrived in 2001 with the devastating Bhuj earthquake. Paradoxically, this disaster provided an unexpected turning point. From the rubble and ruin, a powerful narrative of revival emerged, as non-governmental organizations and designers brought newfound attention to the Bhujodi weaves, catapulting them from village huts onto international runways. This moment of crisis proved to be the catalyst for the craft’s global recognition, showcasing a remarkable phoenix story stitched in extra weft.

III. The Artisan’s Alchemy: The Making of a Bhujodi Saree

The creation of a Bhujodi saree is a meticulous process, anchored by an ingenious piece of technology known as the pit loom. This traditional wooden loom is partially set into a pit dug approximately 2 feet deep into the ground. This unique construction is a marvel of desert-adapted engineering, allowing the weaver to sit at floor level and use their body weight to control the loom’s foot pedals (treadles) with minimal effort. This ergonomic design is a critical element of the craft’s endurance, as it significantly reduces the back strain that would otherwise result from the 8-hour weaving sessions required to produce a single saree. The local names for the loom’s components, such as Fani (the handmade bamboo reed) and Ranchh (the four hand-made shafts), are a testament to the deep-rooted, communal knowledge of the craft.

The signature technique that defines the Bhujodi saree is the extra weft sorcery. Unlike textiles with designs that are either printed on or embroidered later, Bhujodi sarees are unique in that their patterns are “sculpt[ed] into the fabric” during the weaving process itself. This is achieved by manually inserting additional threads between the warp, a method that creates a raised, three-dimensional effect. The weaver uses flat wooden sticks, known as Varach or Patali, to lift specific warp threads, creating the intricate ornamentation that runs horizontally across the fabric. This is an incredibly time-consuming process, with a single saree requiring anywhere from 7 to 15 days of intensive labour. The level of skill required is so immense that it has been described as demanding “near-superhuman precision,” as one misplaced lift can unravel days of work.

The weaving process is a deeply meditative and communal effort, involving several distinct stages. The preparation begins with Tano (yarn alchemy), where women meticulously spin and dye the yarn using vibrant, natural, and AZO-free dyes sourced from the land itself. Next is Sandhani (warp choreography), where the warp threads are carefully measured, starched, and mounted on the loom. The Vanat (weaver’s meditation) is the stage where the men of the community take their place at the looms, their “fingers dancing as motifs take form”. This stage is the culmination of generations of knowledge and patience. The final artistic flourish comes with the Fumka (tassels), which are hand-tied at the end of the pallu, a signature feature that adds movement and texture to the finished product.

IV. The Earth’s Palette: Materials and Motifs

The Bhujodi saree is a tangible expression of its desert origins, with its materials and motifs serving as a direct dialogue with the land itself. The primary fibber of choice is Kala Cotton, an indigenous, organic, and rain-fed variety that is perfectly suited to the arid climate of Kutch.

Lauded as “the desert’s gift,” Kala Cotton is known for its remarkable durability, textured feel, and breathability, making it the ideal fabric for daily wear. Its cultivation is inherently sustainable, using up to 80% less water than conventional cotton and growing without the need for chemicals. A unique claim about this fibber is that it is so skin-friendly it has been found to be “therapeutic” for individuals with skin conditions like psoriasis.

Beyond cotton, the weavers work with other natural fibbers, including coarse Desi wool for its windproof quality and soft Merino wool for warmth. For ceremonial or contemporary garments, they have innovated by blending cotton with wild silks like Tussar, creating a lightweight fabric with a lustrous sheen. Bhujodi kala cotton saree like canvas, Rogan art artist Ashish Kansara make Rogan painting on Bhujodi saree, called Rogan Art Saree.

Table 1: Bhujodi Materials and Their Characteristics

| Material | Characteristics | Use/Season | Sustainability |

| Kala Cotton | Durable, breathable, textured, skin-friendly | Summer, daily wear | Indigenous, rain-fed, organic, uses 80% less water |

| Desi Wool | Coarse, heavy, windproof, durable | Winter, nomadic life | Indigenous, biodegradable |

| Merino Wool | Soft, warm, luxurious handfeel | Winter, ceremonial | Natural fiber |

| Tussar Silk | Lightweight, lustrous, shimmery | Ceremonial, festive | Low chemical use, natural fiber |

| Cotton-Silk Blends | Lightweight, elegant, comfortable | Ceremonial, contemporary | Natural fibers |

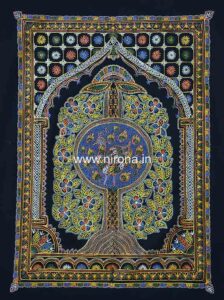

The motifs of the Bhujodi saree are not merely decorative but form a “tribal lexicon” and “secret code” that tells the story of the community, its folklore, and its reverence for nature. These geometric patterns are a visual language that narrates a tale of life in the desert. The Chomak motif, a stylized scorpion, is a potent talisman for protection against evil. The Popati (triangles) represent the jagged hills that frame the Kutch horizon, while the Vank (zigzag) mimics the ephemeral, life-giving flow of a river. The Panchiyo (peacock feathers) suggests blessings carried on the wind, a nod to both the region’s avian beauty and Lord Krishna’s grace. The Dhulki (drum) motif is an echo of the rhythmic dhol beats from Kutchi festivals, and the Zad (tree) symbolizes the deep interconnectedness of the Vankar community with the natural world.

Table 2: Traditional Bhujodi Motifs and Their Symbolism

| Motif Name | Description | Symbolic Meaning | Inspiration Source |

| Chomak | Stylized scorpion | Protection from evil | Tribal Folklore |

| Popati | Triangles | The hills of Kutch | Desert Landscapes |

| Vank | Zigzag | Movement of a river | Nature |

| Panchiyo | Peacock feathers | Blessings and Krishna’s grace | Nature, Tribal Folklore |

| Dhulki | Drums | Echoes of festival beats | Tribal Folklore |

| Mor | Peacock | Divine protection | Nature, Tribal Folklore |

| Zad | Tree | Interconnectedness with nature | Nature |

V. Weaving the Future: Challenges and Preservation

The Bhujodi weaving tradition, despite its celebrated history, faces significant challenges in the modern era. The most immediate threat comes from “power-loom pirates” and industrial manufacturers who mass-produce imitations of Bhujodi designs at a fraction of the cost. These cheap knockoffs undercut the market and make it difficult for artisans to compete. The economic pressure on the weavers is immense, with many earning a modest wage of around ₹10,000 per month for their intense labour. The physical toll of the work, which includes long hours at the loom, sore eyes, and aching backs, further exacerbates the situation, discouraging the younger generation from continuing the craft. Many youths are choosing to leave the village for more lucrative and less physically demanding work in the city.

To combat this onslaught of imitation, the craft has found legal protection in the form of a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, which was granted to “Kutchi Shawls” in 2011. This legal armor is a crucial tool for economic and cultural preservation, as it provides a framework to prevent a third party from using the indication if their product does not conform to the applicable standards. The impact of this protection was immediately felt; until 2012, factories in Ludhiana were mass-producing cheap industrial imitations, a practice that was successfully halted after the GI tag was granted and legal action was taken. This demonstrates that a modern, legal solution was necessary to safeguard a traditional art form against the pressures of industrialization and counterfeiting.

However, the ultimate defence against imitation lies not in legal frameworks alone, but in the inimitable skill of the artisan. The handloom process provides a lasting competitive advantage that cannot be replicated by a machine. While power looms can mimic designs, they cannot recreate the “consistent hand feel” or the subtle tension adjustments of a handloom. The “near-superhuman precision” and the weeks of labour that go into each genuine saree are its most effective forms of trade protection. The preservation of this craft, therefore, hinges on a continued commitment to high-level artistry that cannot be automated.

VI. The Connoisseur’s Guide: How to Spot the Real Deal

For the discerning consumer, a crucial aspect of purchasing a Bhujodi saree is the ability to distinguish an authentic handloom piece from a mass-produced imitation. The following checklist serves as a practical guide to identify a genuine artifact and make an ethical and informed choice.

Table 3: The Authentic Bhujodi Saree: A Buyer’s Guide

| Feature | Genuine Handloom | Mass-Produced Imitation |

| Handfeel | Alive, slightly uneven, and breathable. | Uniformly smooth, often stiff or synthetic-feeling. |

| Weaving Technique | Designs are woven into the fabric itself (extra weft). | Designs are printed, embroidered, or stitched on the surface. |

| Design on Reverse | Patterns are mirrored on both sides of the fabric. | The back is flat and shows no raised patterns or design. |

Tassels (Fumka) | Colourful, hand-tied, and often uneven, a signature flourish. | Machine-made or absent. |

| Price Point | Reflects the 7–15 days of labour; will not cost a trivial amount. | Artificially low, reflecting industrial production. |

| GI Tag | Authentic Kutchi Shawls may have GI certification. | No such certification or tag is present. |

VII. craftcentres.com: A Partner in Preservation

In an era of rampant imitation and commoditization, platforms that prioritize authenticity and ethical sourcing are crucial for the survival of crafts like Bhujodi weaving. craftcentres.com positions itself not merely as a retailer, but as a “guardian of Kachchh’s rich artisanal legacy”. With a history dating back to its founding in 1998 and a digital expansion in 2012, the company has established a long-standing commitment to the craft and its artisans.

The platform’s collection reflects a deep respect for the tradition, offering a curated range that includes Kala Cotton Bhujodi sarees, Tussar silk sarees, and cotton-silk blends. Their product descriptions are a testament to their transparency, detailing the use of eco-friendly Kala Cotton and the precise craftsmanship involved. For example, the Handloom Bhujodi Kala Cotton Saree and Blouse Piece Combo is priced at ₹6,200, a figure that appropriately reflects the labour and material cost of the handloom process, while cotton silk variants range around ₹8,650.

By choosing to purchase from craftcentres, a customer engages in a conscious act of stewardship. The platform’s mission is to champion the communities, traditions, and ecosystems that keep the art forms alive. This commitment transforms a simple transaction into a meaningful contribution to a sustainable future for India’s cultural treasures.

VIII. Conclusion: A Fabric of the Future

The Bhujodi saree is a compelling narrative woven in thread and time. Its journey from a utilitarian blanket for nomadic tribes to a globally recognized piece of art illustrates the resilience and adaptability of the Vankar community. The mastery of the pit loom and the intricate extra weft technique represent a profound and enduring form of human ingenuity that cannot be replicated by industrial machinery. While challenges from imitation and an aging workforce are present, the craft is shielded by the legal protection of the GI tag and, more importantly, by the artisans’ inimitable skill.

Ultimately, the act of acquiring an authentic Bhujodi saree is a commitment to cultural preservation, social responsibility, and environmental consciousness. It is a choice to support the families who dedicate their lives to this craft, to honour the natural dyes that paint its surface, and to ensure that this “woven legend” continues to tell its timeless story for generations to come.